Imagine this scenario: you’ve recently been getting a high number of complaints about defects in your application. Customer satisfaction scores are tanking. Someone notices that test code coverage is around 40%. A mandate is put in place to raise code coverage to over 80%. Surely that must fix the problem!

A month of hard work later, and your code coverage is up. But the defects? Still there. Customer satisfaction? In a death spiral. What gives?!?

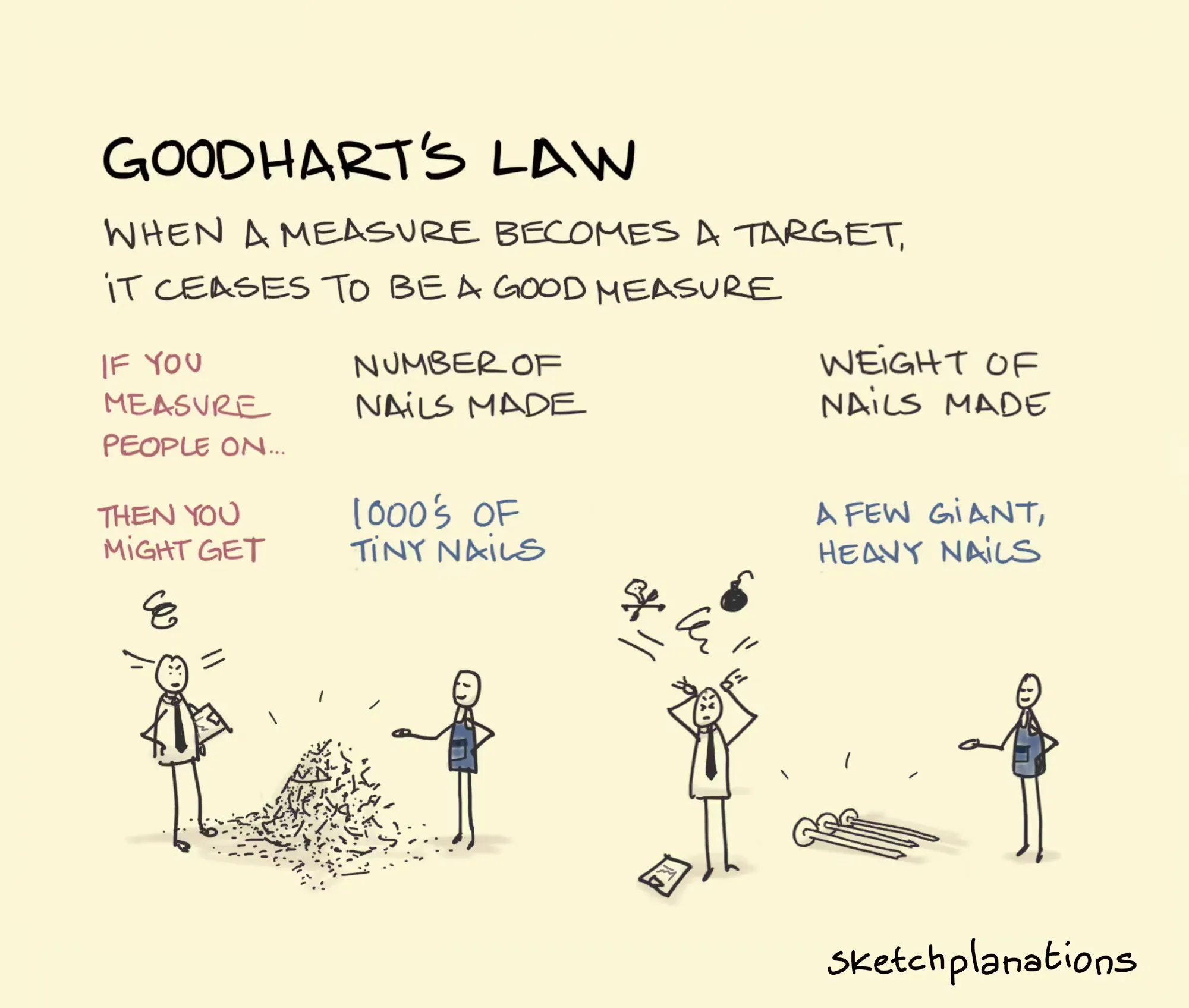

Congratulations, you’ve just discovered Goodhart’s Law. Luckily, there’s still hope for you, but let’s take a look at what just happened first.

Goodhart’s Law states, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”. As soon as we turned the code coverage percentage into the target, we lost sight of the real goal: reducing defects and improving customer satisfaction. Instead, we incentivized developers to maximize coverage (perhaps at all costs).

Code coverage is a flawed metric. It tells us “what you definitely haven’t tested, not what you have”. There’s the potential for developers to write code that covers every line without covering every branch. Even more common, in my experience, is testing flawed, already written code without considering the actual test cases. The goal of tests is to give us confidence in the code we’re writing. This doesn’t mean code coverage is bad. Generally, better code coverage is a positive sign. But on its own, without additional context, it doesn’t definitively tell us anything about the quality of our code.

But this isn’t an article about code coverage. It’s about Goodhart’s Law. And Goodhart’s Law extends to any metric that could become a target. For example, it’s possible to create a web page that gets a 100 on a Lighthouse performance score without being performant. Likewise, you could create another page that gets a 100 accessibility score while being completely inaccessible. We can’t just set targets without having the conversation about the goals we’re trying to achieve.

Now, some of you might be thinking that maybe we just chose the wrong metric. Clearly a performant, accessible site with great code coverage is to help improve customer satisfaction. Right? Maybe…

You then spend months doing everything to improve customer satisfaction. And you succeed. In fact, you exceeded your target and are super excited to let your boss know! Except, instead of receiving the expected praise when you have the conversation, you’re given a pink slip. You gave away too much for free (much to the customer’s satisfaction), revenue plummeted, and the company is on the verge of going out of business. Oops!

Metrics don’t live in isolation. Putting in the effort in service of one metric could degrade another. So you get clever and pick two targets as the priority to track together. But then an unexpected third metric suffers. So you track that with your other priority items, too. Soon enough, everything’s a target, everything’s a priority, and thus nothing is a priority and nothing gets done.

Gwrarrr this is frustrating! I bet you’re about ready to give up on targets and trying to improve your metrics. I wouldn’t blame you either. However, there is a better way. I know of a target metric that you can start using today!

Want to know more? Great! Go ahead and look up your current code coverage. And while you’re at it, maybe your performance and accessibility scores. Or maybe your customer net promoter score. Or revenue. Whatever metric you might want to potentially set a target to improve, look it up and see what the value of that metric is today.

Have it? Awesome. So your new target is now anything better than that. That’s right, we’re not setting an arbitrary target. Instead, we are establishing a benchmark with a directional target of always improving (however iterative that may be) and never going in the opposite direction.

The always improving part seems obvious, but I really want to stress the never going in the opposite direction portion. Doing so is how you introduce tech debt into your systems, diminish the quality of your software, and move further away from the goals that are important to you and your team. In fact, if possible, put an alert or check your key benchmark metrics as part of a continuous integration pipeline. If they are moving in the wrong direction, that needs to be addressed right away.

Now, addressing metrics that are worse than your benchmark doesn’t necessarily mean removing the code or process that may have caused the degradation. That may be the right solution. Having something slightly worse in one area could greatly improve something in a different area. But determining which is the right area to focus on is a human activity. It takes understanding your current metrics, having conversations, creating metric “budgets”, and understanding the impact of what you’re doing.

And that’s the most important part of this exercise — having human conversations and providing context to what we’re doing. Did we add the right test to help catch that tricky bug we were encountering? Is it ok to add that new image if it slightly increases our largest contentful paint but greatly increases our conversions? Identify what metrics are important to your team, be agile in changing what metrics you want to follow, iterate towards always improving, and have human conversations based on your data to set the right context.